Downtown Chicago. Photo credit: Charles Voogd, Wikipedia Commons.

Downtown Chicago. Photo credit: Charles Voogd, Wikipedia Commons.

The information society promises to dematerialise society and make it more sustainable, but modern office and knowledge work has itself become a large and rapidly growing consumer of energy and other resources.

Welcome to the Office

These days, it’s rather easy to define an “office worker”: it’s someone who sits in front of a computer screen for most of the working day, often in a space where others are doing the same, but sometimes alone in a “home office” or with a few others in a “shared office”. In earlier times, many office workers were used not for their knowledge or intelligence, but for the mere objective capacity of their brains to store and process information. For example, “computers” were office workers who made endless calculations with the help of mechanical calculating machines. This category of office workers has become comparatively less important, because inanimate computers have taken over many of their jobs. Most office workers — so-called “knowledge workers” — are now paid to actually think and be creative.

There’s a big chance that you are one of them. Roughly 70% of those in employment in industrial nations now have office jobs. The share of office workers in the total workforce has increased continuously throughout the twentieth century. For example, in the USA, the information sector employed 13% of workers in 1900, about 40% of workers in 1950, and more than 60% of workers in 2000. [1][2] The spectacular and so far unstoppable growth in the number of office workers is believed to have led to a so-called information society, an idea popularised by Fritz Machlup in his 1962 book The Production of Knowledge in the United States, and since then repeated by many others. [3]

Interestingly, there’s no agreement as to what an information society actually is, but the most widely accepted definition is a society where more than half of the labour force engages in informational activities and where more than half of the GNP is generated from informational goods and services. Some say that the information society is characterised by the use of modern IT equipment, but that does not explain the growth of office work during the first half of the twentieth century. Others have argued that there is a transition from an economy based on material goods to one based on knowledge. Their claim is that this shift from the “industrial society” to the “information society” would make the economy less resource intensive. [3][4]

Indeed, unlike workers in manufacturing, service or agricultural industries, office workers don’t really produce anything besides paper documents, electronic files, and a lot of chatter during formal and informal meetings. However, the rise of office work has not lowered the use of resources, on the contrary. For one thing, supporters of the sustainable information society ignore the fact that we have moved most of our manufacturing industries (and our waste) to low wage countries. We are producing and consuming more material goods than ever before, but the energy use of these activities has vanished from national energy statistics. Second, modern office work has itself become a large and rapidly growing consumer of energy and resources.

The Energy Footprint of Office Work

The energy use of office work consists of multiple components: the energy use of the building itself (office equipment, heating, cooling and lighting), the energy used for commuting to and from the office, and the energy used by the communications networks that office work depends on. It also includes people who are not working in the office but who plug in their laptops in a place outside the office, which is also lighted, heated or cooled. As far as I could find out, nobody has ever tried to calculate the energy footprint of office work, taking all these components into account. We know more or less how much energy is used by commuting and telecommunication, but we don’t know how much of that is due to office work.

Most information is available for the energy use of office buildings — the icons of today’s global knowledge economy. However, even in this case information is limited because most national statistics do not distinguish between different types of commercial buildings. The main exception is the US Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS), which is undertaken since 1979 and is the most comprehensive dataset of its type in the world. It further categorises offices into administrative or professional offices (such as real estate sales offices and university administration buildings), government offices (such as state agencies and city halls), banks and financial offices, and health service administrative centers. [5]

Moscow International Business Center. Picture credit: Wikipedia Commons.

Moscow International Business Center. Picture credit: Wikipedia Commons.

The modern, American-style office building — a design increasingly copied all over the world — is an insult to sustainability. Per square metre of floorspace, US office buildings are twice as energy-intensive as US residential buildings (which are no examples of energy efficiency either). [5-10]

In 2003, the most recent year for which a detailed analysis of office buildings was presented (published in 2010), there were 824,000 office buildings in the USA, which consumed 300 trillion Btu of heat and 719 trillion Btu of electricity. [8] The electricity use alone corresponds to 210 TWh, which equals a quarter of total US electricity produced by nuclear power in 2015 (797 Twh with 99 reactors). In other words, the US needs 25 atomic reactors to power its office buildings. [11][12] From 2003 to 2012, the number of US office buildings grew by more than 20%. [5]

How Did we Get Here?

The US office building, which appeared with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution, was initially quite energy efficient. From the 1880s until the 1930s, sunlight was the principal means of illuminating the workplace and the most important factor in setting the dimensions and layout of the standard office building in the US. According to the NYC-based Skyscraper Museum:

“Rentability depended on large windows and high ceilings that allowed daylight to reach as deeply as possible into the interior. The distance from exterior windows to the corridor wall was never more than 28 feet (8.5 m), which was the depth some daylight penetrated. Ceilings were at least 10 to 12 feet (3 – 3.65 m) in height, and windows were as big as possible without being too heavy to open, generally about 4 to 5 feet (1.2 – 1.5 m) wide and 6 to 8 feet (1.8 – 2.4 m) high. If the office was subdivided, partitions were made of translucent glass to transmit light.” [13]

Many office buildings had window accomodating H-, T-, and L-shaped footprints to encourage natural lighting, ventilation, and cooling. This changed after the introduction of fluorescent light bulbs and air conditioning. Produced at an affordable price in the late 1930s, fluorescent lighting provided high levels of illumination without excessive heat and cost. The first fully air-conditioned American office buildings appeared around the 1930s. The combination of artificial lighting and air-conditioning made it possible to design office space much deeper than the old standard of 28 feet. Light courts and high ceilings were ditched, and office buildings were reconceived as massive cubes — which were much cheaper to build and which maximised floor space. [13][14]

Air-conditioning also enabled the most characteristic feature of the modern office building: its glazed façade. From the 1950s onwards, under the influence of Modernist architecture, glass came to dominate in America — early examples of this trend are the Lever Building (1952) and the Seagram building (1958). The US Modernist office building, a cube with a steel skeleton and glass curtain walls, is essentially a massive greenhouse that would be unbearable for most of the year without artificial cooling. Because glazed façades don’t insulate well, energy use for heating is also high. In spite of all the glass, most US office buildings require artificial lighting throughout the day because many office workers are too far from a window to receive enough natural light.

Canary Wharf, London. Photo credit: David Iliff, Wikipedia Commons.

Canary Wharf, London. Photo credit: David Iliff, Wikipedia Commons.

The arrival of electric office equipment from the 1950s onwards further increased energy use. According to the CEBECS survey, “more computers, dedicated servers, printers, and photocopiers were used in office buildings than in any other type of commercial building”. According to the latest analysis, concerning the year 2003, American office buildings were using 27.6 million computers, 11.6 million printers, 2.1 million photocopiers, and 2.5 million dedicated servers. In addition to electricity consumed directly, this electronic equipment requires additional cooling, humidity control, and/or ventilation that also increase energy use. [5, 8]

While heating was the main energy use in pre-1950s office buildings, today cooling, lighting and electronic equipment (all operated by electricity), use 70% of all energy on-site. Note that this ratio doesn’t include the energy that is lost during the generation and distribution of electricity. Depending on how electricity is produced, energy use at the source can be up to three times higher than on-site. Assuming thermal generation of electricity (coal or natural gas), the average US office building consumes up to twice as much energy for electricity than for heating.

Cultural Differences

Technology alone, however, does not explain the rise of the typical air-conditioned office building, nor its high energy use today. Although fluorescent light bulbs and air conditioning soon became available in Europe, the all-glass, cube-like office building remained for a long time a uniquely North American phenomenon. In the 1920s, office work in the USA came under the influence of Frederick Taylor’s ‘Scientific Managament’. Time and motion studies, which had been carried out in factories since the 1880s, were now applied to office work as well. Men with stopwatches recorded the actions of (mostly female) employees with the aim of improving labour productivity.

Taylor’s ideas were translated into office design through the concept of large, open floor spaces with an orderly arrangement of desks, all facing the direction of the supervisor. Private office rooms were abolished. By the late 1940s, American offices resembled factories in their appearance and methods. An example is the use of the dictaphone, which made it possible to separate the conceptualisation and the writing of text. Under the influence of Taylorism, managers began to dictate their writings to a machine instead of a personal secretary, after which the recorded speech was transferred to a central typing room, where dozens or even hundreds of women — under supervision — were typing out one recording after the other. [15, 16]

La Défense, Paris. Wikipedia Commons.

La Défense, Paris. Wikipedia Commons.

In his classic work White Collar: The American Middle Classes (1951), C. Wright Mills paints a not so pleasant image of that time:

The material hardship of nineteenth-century industrial workers finds its parallel on the psychological level among twentieth-century white-collar employees…. The modern office with its tens of thousands of square feet and its factory-like flow of work is not an informal, friendly place. The drag and beat of work, the ‘production unit’ tempo, require that time consumed by anything but business at hand be explained and apologized for… For most employees, work has a generally unpleasant quality. [17]

Although Taylorism left its mark on European offices, it was taken up with less enthusiasm and faced more resistance rooted in tradition than in the US. For example, although the use of the dictaphone and central typing rooms doubled the speed at which documents could be produced, the practice never really caught on in Europe. The open plan arrangement typical of the American office building (which would later evolve into the cubicle arrangement) also spread much more slowly. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Europeans rejected the application of Taylorist principles to office work more strongly, and developed their own type of office building. [15, 16]

The European office building — which British office expert Frank Duffy calls the “social democratic office” — was not focused on efficiency but on user comfort. These buildings, “groundscrapers” rather than “skyscrapers”, were designed like small cities, cut into separate “houses” that are united by internal “streets” or “squares”. They were built with corridors and spacious rooms on either side, all naturally lit and ventilated, with employees working next to a window. The primary focus on user comfort and egalitarianism was a consequence of the fact that office workers in Europe, unlike those in the USA, obtained the right to form democratically elected workers’ councils that could participate in organisational decision making. [15, 16]

The UK followed a different path. In the 1980s, when financial services were rapidly expanding in London, the British completely embraced the US approach, which resulted in large American-like business districts in London, most importantly “the City” and “Canary Wharf”. British employees didn’t receive the new workers’ protection that their colleagues did on the mainland, and business adopted a more harsh, American style of management. [15, 16]

Speculative Buildings

A less visible but crucial difference between the European office building and the US/UK office building is that the first is usually owner-occupied, while the latter is generally a speculative building, built or refurbished to provide a return on investment and rented by the room or floor. However, the US/UK approach is gaining ground. Over the last two decades, speculative office buildings finally started spreading all over Europe, and beyond. Roughly 50% of new office buildings under construction in France and Germany — the largest European markets outside the UK — are now speculative buildings, roughly double their share in the 1980s. [15][18]

This is bad news, because speculative office buildings exclude lower energy alternatives and increase energy use. First, in order to maximise the return on investment, they are usually designed as square or rectangular buildings with deep floor plans and low ceilings, and built as high as planning regimes allow. Naturally lit and cooled buildings require a more horizontal build and higher ceilings, both aspects that conflict with maximising floorspace.

Frankfurt, Germany. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Frankfurt, Germany. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

A second problem with speculative office buildings is that those who design them don’t know who will occupy the finished spaces. “As a result, developers and letting agents focus on the ‘needs’ of the most demanding tenants, and hence what is required for an office to be marketable to any tenant”, write the authors of a recent study that looks into the energy demand of UK office buildings — and concludes that 92% of such buildings are over-provisioned. Lighting, cooling and heating systems are attuned to unrealistic occupancy rates and are consequently producing more light, heat and cold than is necessary. [19][20]

One way in which UK developers and letting agents deal with uncertainty is by following the guidelines of the British Office Council (BCO). These guidelines are based on extensive industry research about what level of technical provision is considered necessary in a high ‘quality’ office if occupants’ ‘needs’ and expectations are to be met. However, even according to the BCO’s own research, mean utilisation rates of offices are 60-70% of the advised occupancy rates. This has enormous consequences for energy use, as the authors of the study explain:

An assumption of the amount of lighting and small power delivered to every square metre of the office floor space is based on the (over) assumed occupancy density and requirements of occupants, and these three factors — human bodies, lights and the equipment that is presumed to be used to consume this small power on the floor — create a modelled heat gain.

Assumed peaks for this heat gain are then taken into consideration and used as a multiplier to produce a cooling requirement of a certain amount of W/m2, and the occupational densities also provide an estimate of the numbers of people who require ventilation of 12 litres of air to be provided every second to every 10m2 assumed workplace or person. At this point, energy demand is designed-in: electricity plant and HVAC systems are sized, and infrastructures are wired in, to supply for these over-assumptions. [19][20]

While the BCO guidelines were originally designed to tame an “arms race” in office specifications during the London office building boom of the 1980s, the study shows that they have instead locked-in a certain level of (over)provision of services that excludes the use of low energy alternatives. In the competition for office tenants, developers and letting agents have turned what were supposed to be maximum levels for provision into minimum levels for the “quality” office, which are increasingly exceeded.

Interviews with market players also show that they adopt informal quality standards, such as the importance of glassy façades, marble toilets, or spacious and impressive entrances and lobbies, resulting in highly standardised buildings. In other words, the air-conditioned glass office building has become such a strong cultural symbol that it is now a standard by itself. [19][20]

The Promise of Remote Working

If the high energy use of office work is questioned at all, it’s usually followed by the proposal to work outside the office building. At least since the 1980s, home working has been touted as a trend with potential environmental benefits. Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave (1980) predicted that in the near future it would no longer be necessary to build offices because computers would enable people to work anywhere they wanted. In 1984, when personal computers had become common equipment in offices, British office expert Frank Duffy stated that “many office buildings quite suddenly are becoming obsolete”. [15]

Financial District, Downtown Toronto. Paul Dex, Wikipedia Commons.

Financial District, Downtown Toronto. Paul Dex, Wikipedia Commons.

Obviously, no such thing happened: in spite of the personal computer, there are now more office buildings than ever before. However, the utopian vision of a radically changed work environment is still among us. Since the arrival of mobile phones, portable computers and the internet in the 1990s, the focus has shifted to “remote” or “agile” working, which includes working at home but also on the road and in so-called third places: coffeeshops, libraries or co-working offices. [20] These concepts suggest that offices will become meeting places for ‘nomadic’ employees equipped with mobile phones and laptops, how the office will become a more diverse and informal environment, or how in the near future offices may no longer be necessary because we can work anywhere and at any time. [15] According to a 2014 consultancy report:

“The term ‘office’ will become obsolete in the coming years. The modern workplace evolves into more of a shared workspace with flexible working arrangements that acts as more of a hub for workers on the go than an official place of work. The vast majority of jobs in most organisations can be accomplished from virtually any PC or mobile device, from just about anywhere”. [21]

Frank Duffy, building further upon his 1980s predictions, writes in Work and the City (2008):

“The development of the knowledge economy and achievement of sustainability will both be made possible by the power of information technology… Office work can be carried out anywhere… In the knowledge economy more and more businesses, both large and small, will be operated as networks, depending at least as much on virtual communications as on face-to-face interactions. Networked organisations do not need to operate, manage or define themselves within conventional categories of workplaces or conventional working hours.” [16]

Although remote working is indeed increasing, it is not a spectacular trend so far. For example, in the UK in 2014, about 14% of those in employment reported their home as their main place of work, an increase of only 2.8% since 1998. More than 25% reported that they sometimes work from home as part of their main job. [22][23] However, these data relate to all jobs, not just office work, and most home workers are active in agriculture and construction. For office (and retail) workers in particular, the numbers vary between 8% and 18% of the workforce, depending on the sector. ICT workers have the highest shares of office workers who “usually” work from home. [24]

Would Remote Working Lower Energy Use?

On the face of it, more people working outside the office has obvious potential for energy savings. Home workers don’t have to travel to and from the office, which can save energy — after all, commuting has also become energy-intensive since the democratisation of the car in the 1950s. Furthermore, home office workers tend to use less energy for heating, cooling and lighting than they do in the office, a finding that corresponds with the fact that office buildings consume double the energy per square metre of floorspace compared to residential homes. [22]

However, there are many ways in which the environmental advantages of remote working can disappear or become disadvantages. First, remote workers make use of the same office equipment, the same data centers and the same internet and phone infrastructure as people working in an office — and these are now the main drivers behind the increasing energy use of office buildings. In fact, a networked office would surely increase energy use by communication services, because face-to-face meetings at the office are replaced by virtual meetings and other forms of electronic communication.

In Work and the City, Frank Duffy recalls his participation in a videoconferencing talk, expressing his awe for the quality of the experience. What he doesn’t seem to realise, is that the Cisco Telepresence system that he was using requires between 1 and 3 kW of power (and 200W in standby) at either side [25], plus the energy use of routing and switching all those data through the network infrastructure.

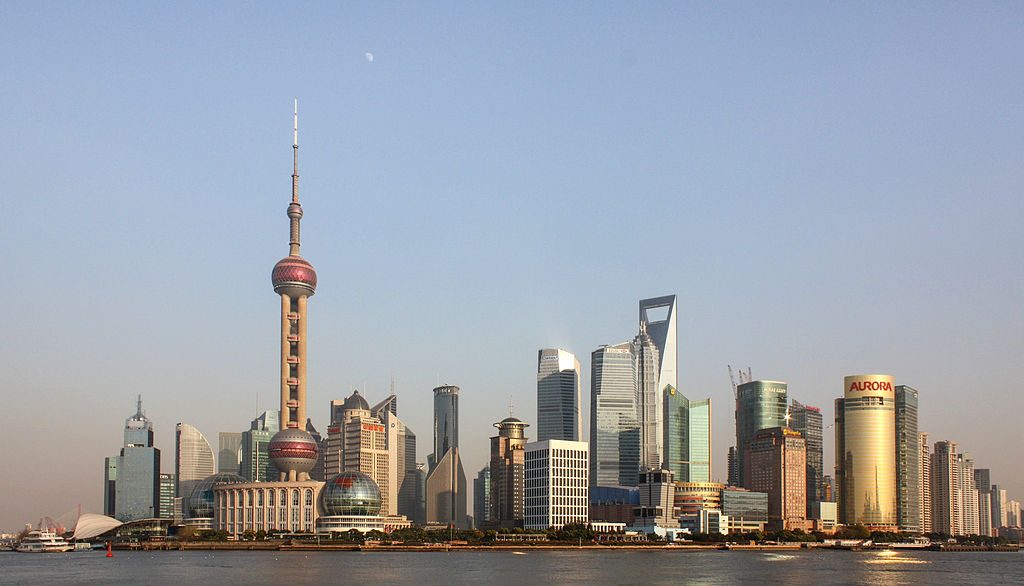

Lujiazui, Shanghai. Patrick Fischer, Wikipedia Commons.

Lujiazui, Shanghai. Patrick Fischer, Wikipedia Commons.

Second, if work is done not at home but in third places, people might actually increase their energy use for transport when they visit different working spaces during the day. They might work from home in the morning and drive to the office in the afternoon, or they might go to the office in morning and to a co-working space later in the day. Likewise, if organisations shorten the distance between the office and the office worker by inviting them to work in shared spaces closer to their home, employees might actually decide to go live further away from their new working space, and keep the same time budget for commuting. [20]

Third, for an employee working at home, on the road, or in a third place, the heating, cooling and lighting of that alternative workspace is now often an extra load because his or her now empty space in the office is still being heated, cooled and lit. In most cases, today’s home and remote workers occasion additional energy consumption. [22] This problem is recognised by the supporters of remote working, who stress that office buildings have to adapt to the new reality of the networked office by reducing floorspace and increasing the occupancy rates. This can happen through “hot-desking”, sharing a smaller amount of desks between office workers who decide not to work at home — and hope that not everybody will show up at the same time.

Noel Cass, who investigates energy demand in offices for the UK’s Demand Centre at Lancaster University, has his doubts about this approach:

“Hot-desking” requires the depersonalisation of the desk, as if it was a coffee bar or a library, and that’s easier said than done. Internet companies such as Google and Yahoo, who pioneered hot-desking arrangements and whose productivity is the rationale behind this trend, have gone back to giving each employee their personal space. In fact, these companies not only left behind the “non-territorial” office, they also have recognised that productivity is best secured by physical co-presence, discouraging telecommuting.

Office spaces now tend to be conceptualised as a ‘destination’ with increasing amenities on the job, in an effort to attract and retain talent and encourage them to spend more time there. Examples are domestic-like interiors, gym facilities, indoor swimming pools, dry cleaners, or dentists on site. So, who knows, instead of working at home, the future could be living at the office. Obviously, increasing amenities at the office might negate the energy savings obtained by fewer and shared office desks. [20]

In conclusion, office work will always include buildings, commuting, office equipment and a communication infrastructure. The focus on the location of office work — at home, in the office, or elsewhere — conceals the real cause that impacts energy use: the high energy use of all its components.

If the commute happens, or could happen, by walking, biking, or taking a commuter train, instead of by car, the energy use advantage of working at home would be zero or insignificant. Similarly, if an office building is designed in such a way that it can be naturally lit and cooled, like in the old days, working from home would not save energy for cooling and lighting. Finally, the use of low energy office equipment and a low energy internet infrastructure would lower the energy use regardless of where people are working. In short, for energy use it doesn’t matter so much where office work happens. What really matters is what happens at these places and in between them.

How Much Office Work Do We Need?

In his 1986 book The Control Revolution, James Beniger states that there is a tight relationship between the volume and speed of energy conversion and material processing in an industrial system on the one hand, and the importance of bureaucratic organisation and information processing, in other words, office work, on the other hand:

Innovation in matter and energy processing create the need for further innovation in information processing and communication — an increased need for control. Until the nineteenth century, the extraction of resources, even in the largest and most developed national economies, were still carried out with processing speeds enhanced only slightly by draft animals and wind and water power.

So long as the energy used to process and move material throughputs did not much exceed that of human labour, individual workers could provide the information processing required for its control. The Industrial Revolution sped up society’s entire material processing system, thereby precipitating a crisis of control.

As the crisis in control spread through the material economy, it inspired a continuing stream of innovations in control technology — a steady development of organisational, information-processing, and communication technology that lags industrialisation by perhaps 10 to 20 years. By the 1930s, the crisis of control had been largely contained. [1]

Although Beniger makes no reference whatsoever to sustainability issues, what he suggests here is another strategy to lower the energy use of office work: reduce the demand for it. If office work depends on the material and energy throughput in the industrial system, it follows that reducing this throughput will lower the need for office work. A slower, low energy, and more low-tech industrial system would decrease the need for control and thus for office work. An economy with smaller organisations operating more locally, would need less office work.

Cuatro Torres Business Area, Madrid. Xauxa Hakan Svensson, Wikipedia Commons.

Cuatro Torres Business Area, Madrid. Xauxa Hakan Svensson, Wikipedia Commons.

By the 1900s, all management techniques and office tools that would be used for the next 70 years had been invented. James Beniger was not impressed by the arrival of the digital computer, which was becoming ubiquitous in offices when he wrote his book:

Contrary to prevailing views, which locate the origins of the information society in WWII or in the commercial development of television or computers, the basic societal transformation from industrial to information society had been essentially completed by the late 1930s.

Microprocessing and computer technology, contrary to currently fashionable opinion, do not represent a new force recently unleashed on an unprepared society but merely the most recent installment in the continuing development of the control revolution.

Energy utilisation, processing speeds, and control technologies have continued to co-evolve in a positive spiral, advances in any one factor causing, or at least enabling, improvements in the other two. Furthermore, information processes and flows need themselves to be controlled, so that informational technologies must continue to be applied at higher and higher layers of control — certainly an ironic twist to the control revolution. [1]

Our so-called information economy mainly serves to manage an ever faster, larger and more complex production and consumption system, of which we have only outsourced the manufacturing part. Consequently, without the information economy — without the office — the industrial system would collape. Without the industrial system, there would be no need for the information society or the office — in fact, office work could be like it was before 1850, when the biggest bank in the US was run by just three people with a quill. [1]

The sustainable image of the information society — as contrasted to the dirty image of the industrial society — is entirely built on an obsession with dividing energy use into different statistical categories, fiddling around with figures on electronic calculating tools. In other words, it’s a product of office work, hiding the true nature of office work.

Kris De Decker

This is a slightly extended version of an article also available at Low-tech Magazine.

Sources:

[1] The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society, James Beniger, 1986.

[2] The Growth of Information Workers in the US Economy, Edward N. Wolff, in “Communications of the ACM, October 2005/Vol.48, No.10, 2005.

[3] Theories of the Information Society (Third Edition), Frank Webster, 2006.

[4] Sustainability and the Information Society [PDF], Christian Fuchs, IFIP International Conference on Human Choice and Computers, 2006.

[5] 2012 Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS), U.S. Energy Information Administration.

[6] A review on Buildings Energy Consumption Information [PDF], Luis Pérez-Lombard, José ortiz, Christine Pout. In “Energy and Buildings 40 (2008), pp.394-398.

[7] Power Density: A Key to Understanding Energy Sources and Uses, Vaclav Smil, 2015.

[8] Office Buildings, CBECS, 2010.

[9] BSD-152: Building Energy Performance Metrics. Building Science Corporation, 2010.

[10] U.S. Energy Use Intensity by Property Type, Technical Reference [PDF]. Energy Star, 2016.

[11] US Nuclear Power Plants, Nuclear Energy Institute.

[12] A Look at the US Commercial Building Stock: Results from EIA’s 2012 Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CEBECS). US Energy Information Administration, 2015.

[13] Downtown New York: The Architecture of Business / The Business of Buildings. Virtual Exhibition. The Skyscraper Museum.

[14] Losing Our Cool, Stan Cox, 2010.

[15] The European Office: Office Design and National Context, Juriaan van Meel, 2000.

[16] Work and the City, Frank Duffy, 2008.

[17] White Collar: The American Middle Classes. C. Wright Mills, 1951.

[18] Office Buildings Go Up on Mere Speculation, Alessio Pirolo, The Wall Street Journal, October 7, 2014.

[19] Standards, Design and Energy Demand: The Case of Commercial Offices. James Faulconbridge & Noel Cass, 2016. Paper prepared for DEMAND Centre Conference, Lancaster, 13-15 April 2016.

[20] Papers in preparation, Noel Cass, The Demand Centre, Lancaster University, UK.

[21] Study: The Traditional Office Will Soon be Extinct. PC World, Tony Bradley, June 17, 2014.

[22] The Practice of Working from Home and the Place of Energy [PDF], Sam Hampton. Paper prepared for DEMAND Centre Conference, Lancaster, 13-15 April, 2016.

[23] Characteristics of Home Workers, 2014 [PDF]. Office for National Statistics, June 2014.

[24] Four million people are now homeworkers but more want to join them. TUC, June 5, 2015.

[25] Immersive TelePresence. Cisco.